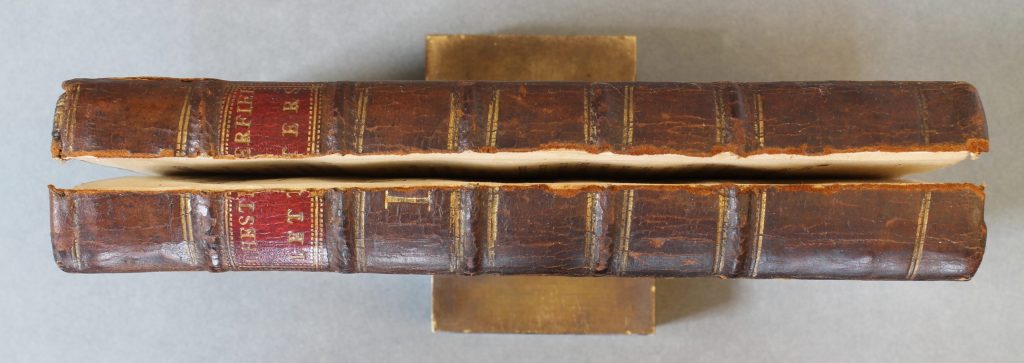

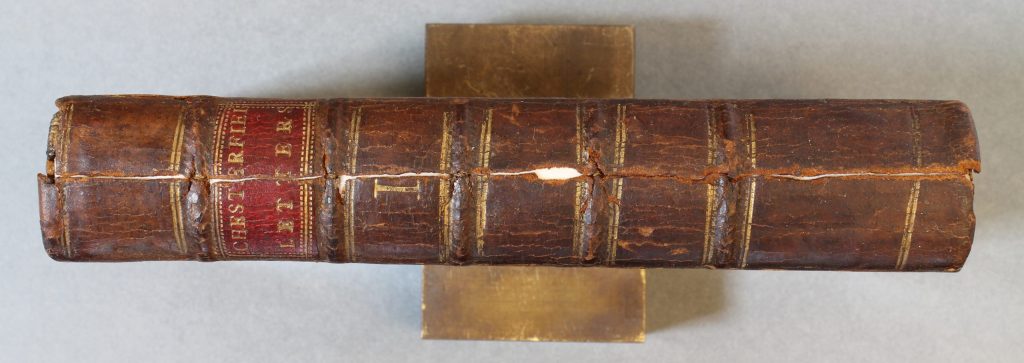

Lord Chesterfield’s Letters (Dublin, 1776) is a fairly typical 18th century in-board binding, sewn on five raised cord supports, and fully-covered in smooth, sprinkled, brown calf over boards. As is common of books of this period from the British Isles it has thin degraded leather, brittle animal glue on the backs of the sections, and no spine linings. The result is a very rigid inflexible spine – ironically this style of binding on raised cords with a tight back is sometimes call ‘flexible’. Consequently, when this little book was forced open it simply fractured into two halves!

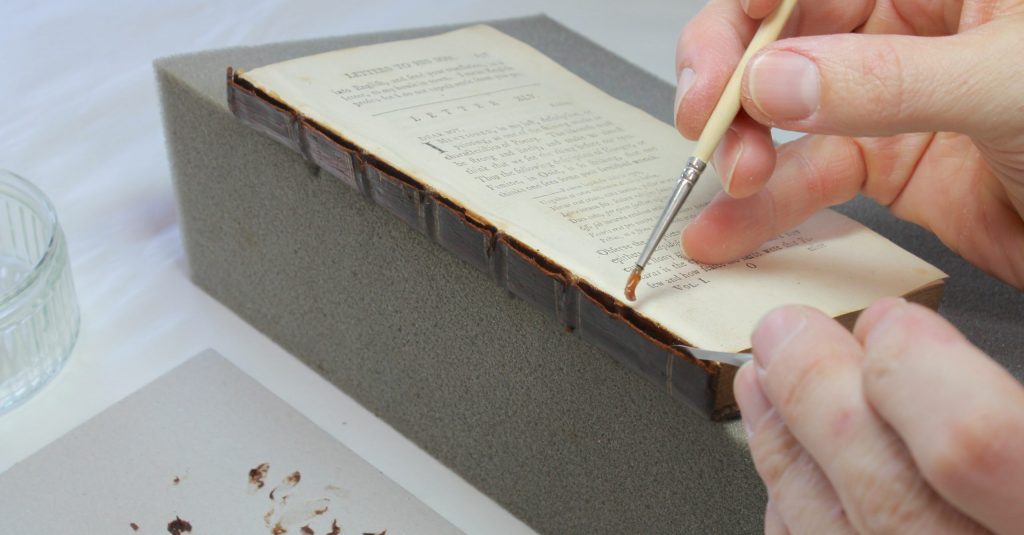

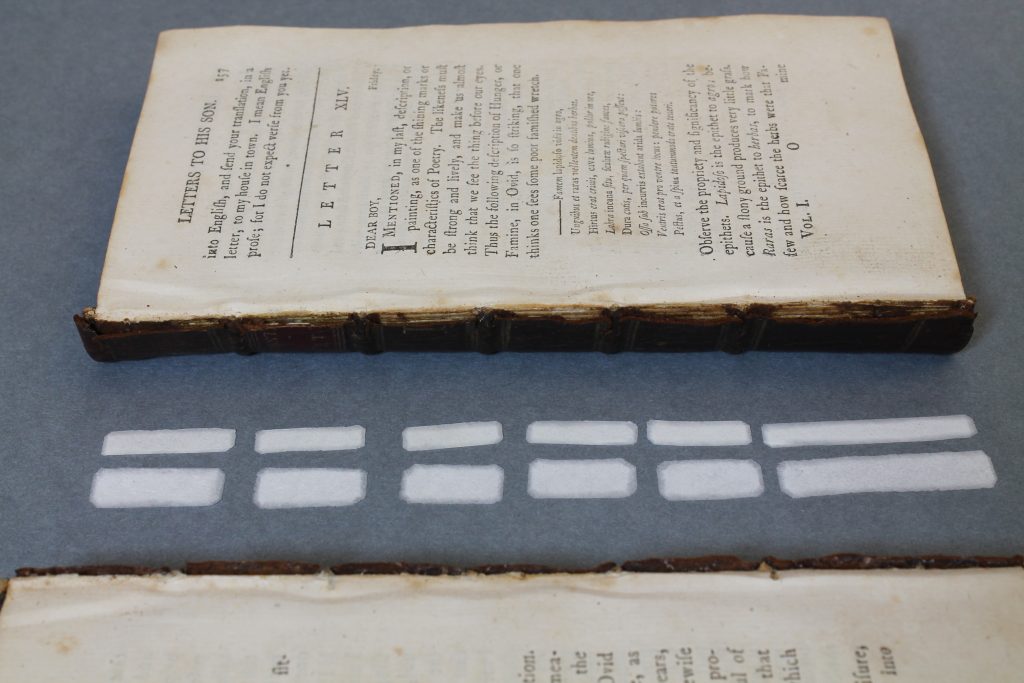

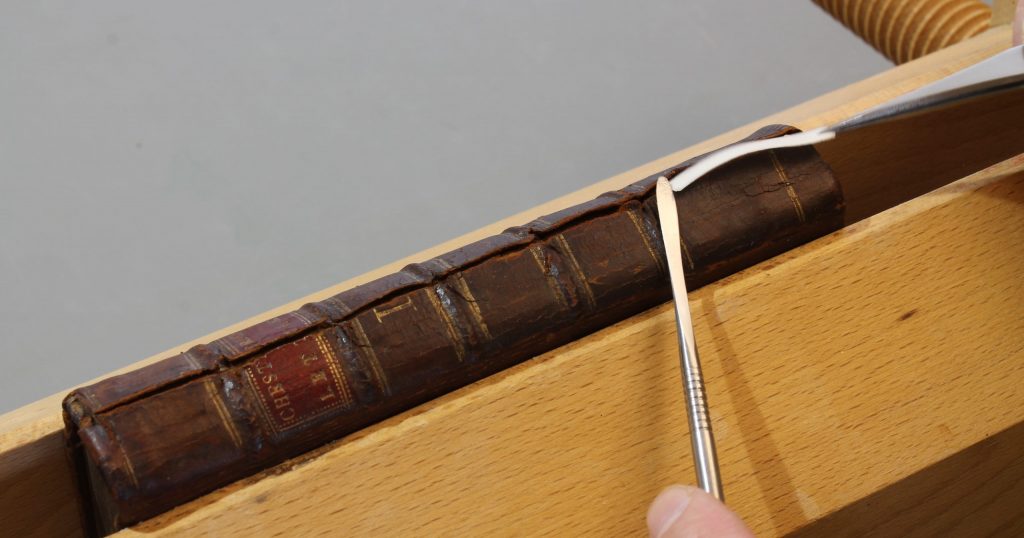

My job was to reunite the two halves; with a brief of preserving the original binding. There was little chance of repairing the split cords or the endbands (without adversely altering the binding), so I was limited to spine linings inserted under the old leather between the cords. I wanted the mechanics of the repair to function as well as possible so started to consider how I could spread the stresses over the join. For this I took inspiration from a rather unusual source: vehicle leaf spring suspension. These work by layering multiple plates of steel of progressive lengths; the effect of this is more resistance in the middle than at the edges. I chose parchment for the lining material for its relative rigidity and strength compared to its thickness, and applied the leaf spring concept with multiple linings of increasing width. The following is a brief account of the treatment.

In conclusion, the treated binding is still vulnerable and weak at the split; however, it is now back in one piece and the repair appears to have bridged the gap sufficiently for careful use. The parchment spine linings have avoided the need for rebinding and preserved the aesthetic of the original 18th Century spine. It was fortunate that the spine leather lifted relatively easily (something which is not always possible), as this provided good access to effect the repair. I was limited to two layers of parchment on the spine of this book due to its size – more than that and the linings would have been too bulky and visually obtrusive on the book. Certainly there is some scope to explore this technique further.

Thank you to Joanne Wilson, Museums and Heritage Officer, for The Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum, for permission to use the photographs.

http://www.samueljohnsonbirthplace.org.uk/Collections_6124.aspx

Arthur Green, February 2020

Fascinating and very informative! Thank you for sharing the images to go along with excellent descriptions.

Thanks Corinne, I’m glad you enjoyed this post and found it useful.