The introduction of the first mass produced, embossed, starched fabric for covering books is generally attributed to Archibald Leighton in the 1820s. The development of book-cloth was a catalyst for the movement away from in-board binding towards a case bound structure and the term ‘cloth binding’ has now become almost synonymous with case binding. However, there was a trend in English bookbinding for covering books in cloth that predates mass produced book-cloth by some fifty years. A coarse brown cloth, or canvas, started to be used on cheaper books, and in particular school books, from the early 1770s. It’s thought that the use of canvas as a covering was quite common, but few examples now survive.

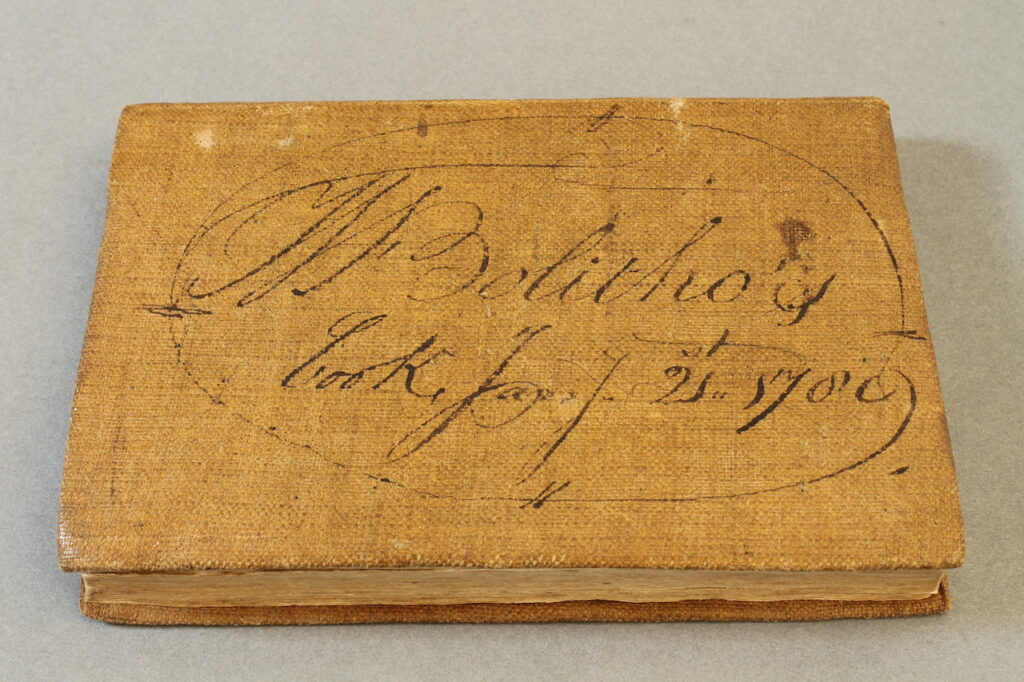

I recently bought a copy of Aesop’s Fables (1783) which appears to be a really good example of a ‘canvas binding’. It’s a small (H:161mm W:110mm) school book in Greek and Latin; there is also a pleasing inscription in iron-gall ink across the entire right (back) board that provides some nice evidence of its ownership and likely use for study.

For anyone studying the history of bookbinding, A History of English Craft bookbinding Technique by Bernard C. Middleton is never a bad starting point. So I was delighted when I read the entry Canvas Bindings to find Bernard describe “An example in my possession, on a 1789 edition of Aesop’s Fables in Greek and Latin”[1] My copy is printed six years earlier but is otherwise identical: it’s stabbed (rather than sewn) on two tawed thongs laced into thin rope boards; it’s rounded but not backed with no spine linings; and is covered in-boards (therefore not a case) in canvas. I also agree with Bernard that “The appearance of the material is not altogether unpleasing to my eye”, though apparently “it did not find favour at the time for comparatively few examples are known.”

The book was described by the seller as in ‘very poor condition’; the paste downs are lifting and the turn-ins are not square. However, the text-block is clean and without tears, the leaves are all held in place securely and the covering canvas is strong without any damage at the joints or caps; so I certainly wouldn’t describe the book as ‘very poor condition’. I believe what has happened is that condition has been confused with quality. The person describing the book may not have been aware of its significance, they saw a drab looking book and assumed it was of little value.

[1] Middleton, Bernard. A History of English Craft Bookbinding Technique. 4th rev. ed. New Castle, DE; London: Oak Knoll Press; The British Library, 1978. (or any later edition) p.132

Arthur Green, Sept. 2022

very interesting Arthur – thanks for posting – you appear to have found a real bargain. In Bernard’s book – your reference (1) – Bernard draws attention to Douglas Leighton’s article in The Library, Fifth Series – Vol. III No. 1 for June 1948 – a paper titled ‘Canvas & Bookcloth’ – An Essay on Beginnings – which gives much information on early C19 materials for covering books. It really is an interesting essay and worth reading if you’re into the history of trade bindings from that period. I can only assume that the similarity of names (Archibald and Douglas Leighton), though amusing, is pure coincidence.

There appears to be some confusion arising from Bernard’s own comments in his book ………… Looking at the Second Supplemented Edition of 1978, he speaks of an example in his possession – the Aesop’s Fables you refer to – but in footnote No. 1 he speaks of the example shown in The Library as being “the only one known to me”.

It’s possible that in the intervening years between the 1963 first edition and the later 1978 printing, Bernard appears to have acquired his ‘Aesop’s’ example, but the text looks not to have been corrected from 1963.

I’ve no idea as to the whereabouts of Bernard’s own copy of Aesop – it may well have gone to the States with most of his other material.

Douglas Leighton, in his paper written for The Library, gives a short list of other canvas bindings that he was aware of and their locations as at 1948, but no idea as to their whereabouts now.

Thanks again, very envious of your find, but that’s the reward we get for having studied a subject for many years, and we deserve the perks that come with expertise.

Hi Paul, I’m glad I peaked your interest; And thanks for a considered response. Yes it was a good find wasn’t it! It’s amazing what you can still find if you look hard enough. It will be a welcome addition to my teaching collection so will be getting an airing at my ‘Understanding Bookbindings‘ seminar next year. I’ll have to check the Leighton article, I’d interested to know how may Canvas bindings he listed.

Thank you for this

Glad you found it interesting.

Could your book be the very one Middleton describes? The publication date of yours is 1783 but the inscription on the binding can be read 1789. Could this be what he meant?

Hi John, thanks for your comment. Wouldn’t that be a nice thought. We only lost Bernard a few years back, at which point he was very well known, so I suspect that it’s unlikely that his collection has been dispersed and sold off.