Back in January 2022, Lena and I decided to ease into the new year with a trip to see our friend Trevor Lloyd MBE in Ludlow. We were welcomed into Trevor’s bindery and our questions were all answered with openness and patience. Insightful and enjoyable as our trip was, my main reason for visiting was to give Lena[1] the opportunity to see Trevor’s bindery which is housed in a double fronted Georgian shop situated in the centre of Ludlow.[2] The walls of the right-hand room are adorned with scores of gold-finishing tools, a craft for which Trevor is quite rightly considered preeminent. The bindery is the manifestation of Trevor’s long and distinguished career as an antiquarian book restorer as well as finisher, and, as Trevor put it “I don’t see a shop like this being replicated again any time soon”.

To the untrained eye the bindery could be confused with an exhibit in a working museum, the sort one might find at Beamish or The Weald & Downland Living Museum. It is, of course, not a museum but a working commercial bindery. What makes it special is Trevor’s understanding of the history of bookbinding; it’s a truly special place full of some rare bookbinding tools and machinery. Easy as it is to be charmed by the finishing tools, on this occasion it was some sets of tying-up boards (a basic wooden tool) that caught my eye. The boards I spotted had the beautiful patina of an English oak coffer and the look of tools that had been in use for hundreds of years… what a treasure!

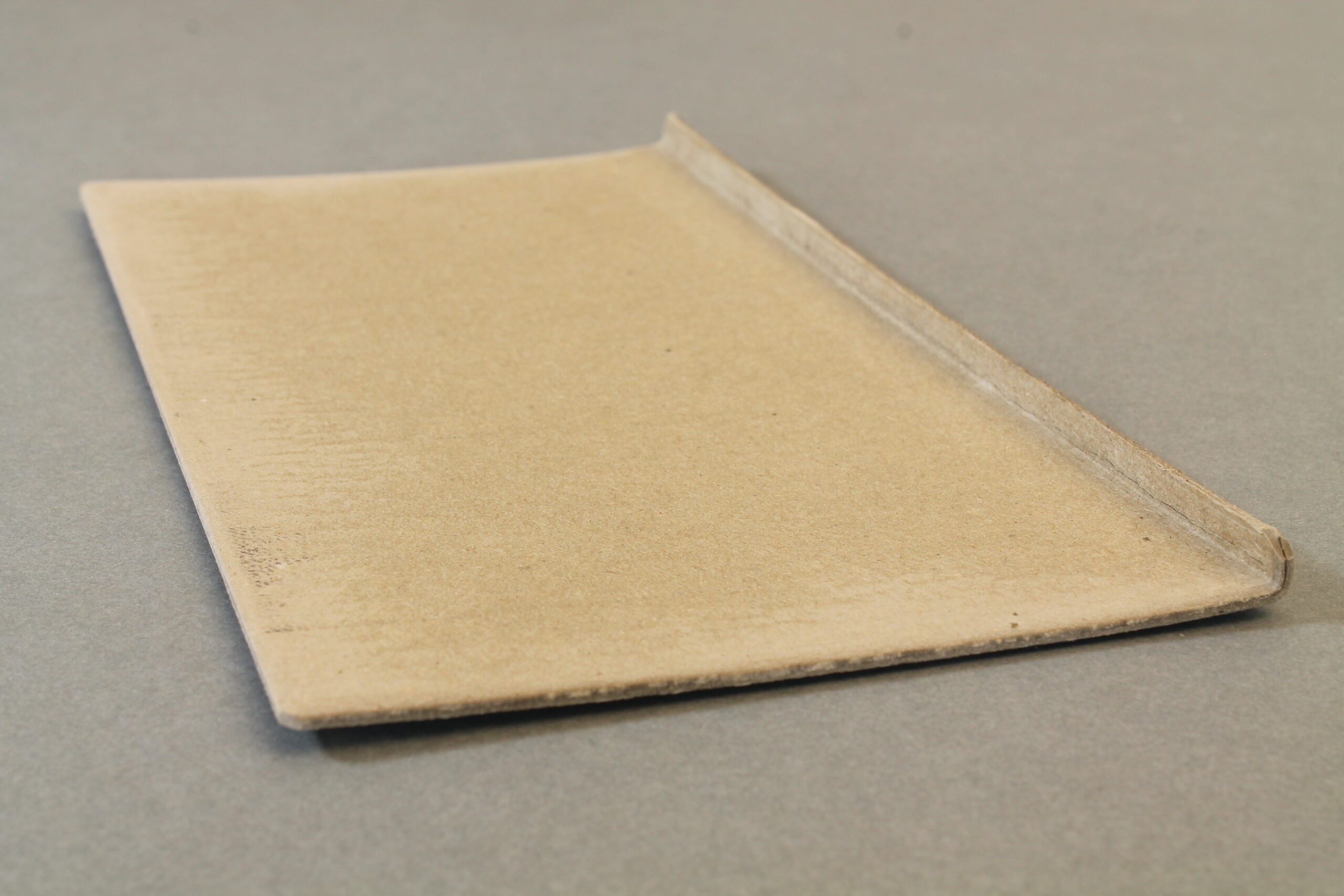

Tying-up boards are flat batons of wood (with a short lip on one of the long edges) that are fitted to the fore-edge of a book during covering while the leather is still damp. Cord is then wrapped tightly around the book cinching the leather either side of the raised cords ensuring that low-tack, slow-drying paste sticks the leather to the spine at this crucial juncture. Their primary function is to preserve the fore-edge of a book from unwanted cord marks when covering.

To understand how tying-up boards were used, it’s worth taking a moment to briefly describe the history of how bookbinders dealt with molding leather over the spine of a book. As with much of the study of English bookbinding, the subject is rather skewed by the dominance of the Victorian model of teaching the craft. The creation of those beautiful sharp, false raised-bands that we are familiar with on the spines of Victorian leather bindings are achieved with thinly pared leather and the use of band-nippers, or band-sticks. What I’m interested in here is the period before that.

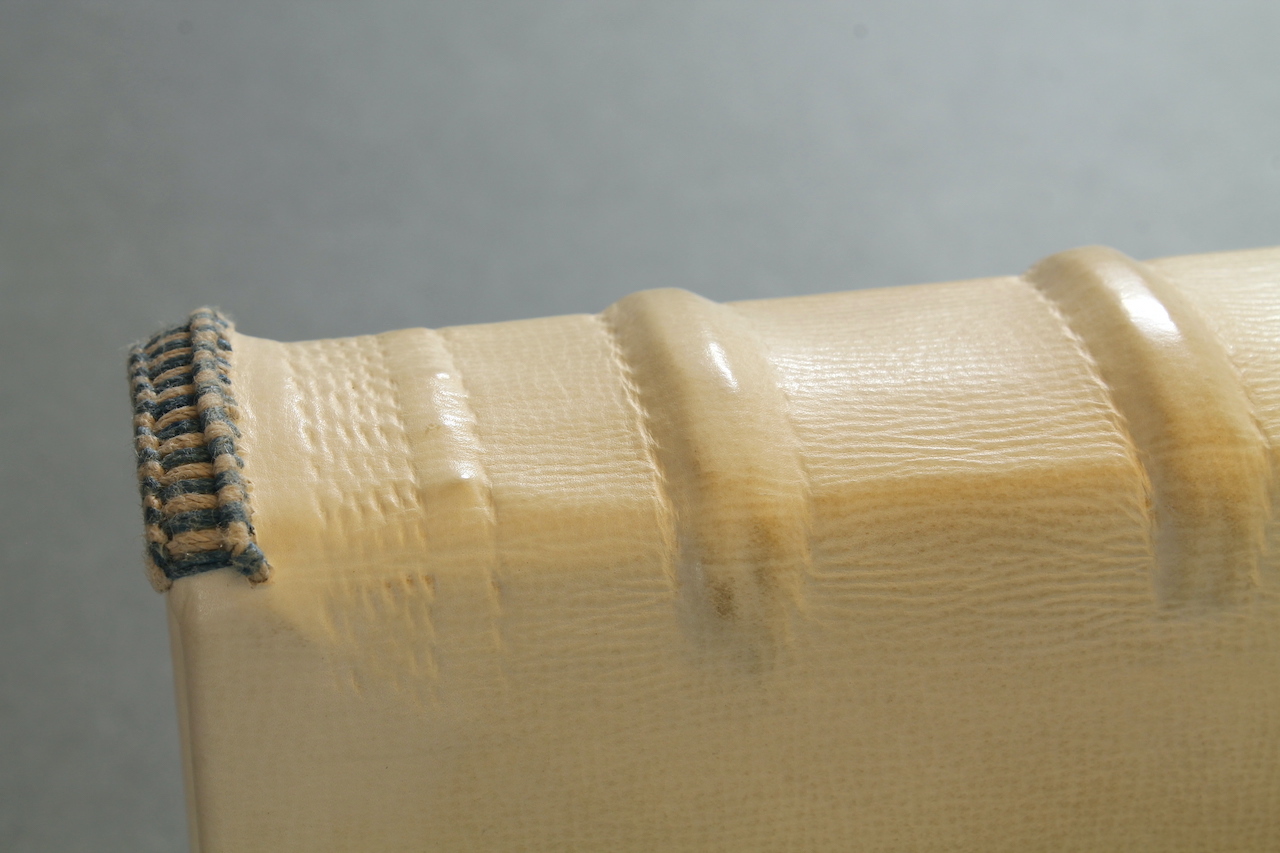

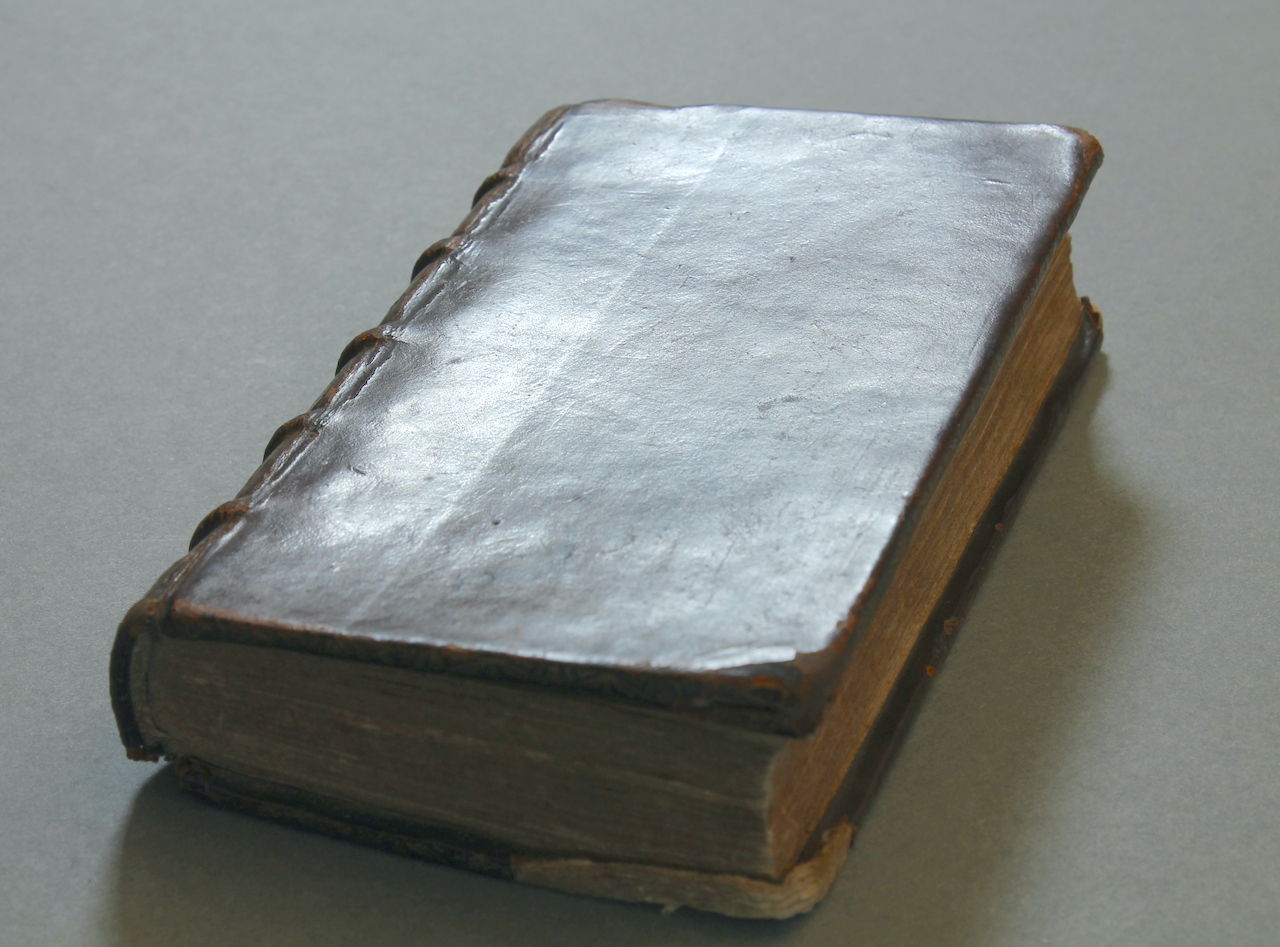

If we look at post-conquest English bindings, such as those that may be loosely classified as ‘Romanesque’ in structure, then these do not typically show evidence of tying up; the covering material sits loosely over the wide bands giving the spine an almost flat profile.[3] However, if we move forward to Gothic bindings then it is common to see that the covering material has been marked, where string or cord has been wrapped around the bands whilst the skin is still wet from paste. The result is the familiar, well-defined raised bands that became ubiquitous on leather bindings thereafter.[4]

I have observed a number of examples of fourteenth and fifteenth century English gothic bindings where cord marks can clearly be seen either side of the bands but also at the fore-edge; clear evidence that the books were tied up but also evidence that tying-up boards were not yet in use. My feeling is that the introduction of tying-up boards coincides with the increased application of blind-tooling — or stamping — in the second half of the fifteenth century. As bookbinding became more refined and decorative, more care was taken and by the sixteenth century those tell-tale marks at the fore-edge start to disappear. Cord marks from tying-up are often misidentified as blind-tooling; however, on close inspection the twisted cord marks indicative of tying-up are different from the even thickness of a tooled blind line.

Evidence that tying-up boards were in common use in the eighteenth century can sometimes be found in a line or indentation across the face of the book board, where the binder has carelessly tied the book too tight. According to Middleton “virtually all books with raised thongs or cords — whether folios or twelvemos —were tied up until the early nineteenth century.”[5] What changed in the early nineteenth century was the introduction of the hollow back and neat false raised-bands.

Now this might all sound a bit academic, but it is these details that make the difference if you are called upon to conserve or restore a book. If you use the right tools, materials and techniques when working on an historic binding then the chances are that your work will look in keeping with the period of the book. In short then, tight-back bindings with raised cords were tied up; and false raised bands on hollows used band nippers.

Back to our trip to Ludlow… On our return I consulted Middleton, and with some advice from Trevor made up some tying-up boards from mill board. [6] These prototypes worked well enough but I found that they had a tendency to warp as they absorbed moisture from the damp covering leather. So I started looking through my collection of bookbinding manuals for inspiration and came across an image in Hasluck. [7] It shows a pair of traditional wooden backing boards being used to tie-up a book. It seems like a rather difficult operation keeping everything in place, but I suspect that a skillful trade binder doing this everyday would have had little trouble. At this point the penny dropped, and I realised that Trevor’s tying-up boards were adapted backing boards. Once I thought about it, it was obvious that whoever made these boards simply used what materials (or in this case existing tools) they had to hand. It also explains why there are few historic accounts of tying-up boards – as these were one and the same as backing boards. Adapting backing boards has a number of obvious advantages…

- They are readily available to many bookbinders, and require little modification;

- Using old boards means the wood is well seasoned avoiding any warping;

- Backing boards already come in convenient standard book size lengths;

- The wedge shape concentrates the pressure at the fore-edge (hopefully), avoiding any marks on the sides of the book.

So I set to modifying some old sets of wooden backing boards to create four new pairs of tying-up boards for the studio (two 9”, one 10” and one 15”). Firstly the thick edges of the boards needed squaring off to remove the wedge shape. This was done on a band-saw with help from our local carpenter. Then strips of wood were attached along the edge (giving a lip of approximately 7mm for the smaller boards and 9mm for the large pair) and fastened with countersunk screws. I then sanded smooth the sharp top edge to avoid marking the leather. The final job was to cut notches across the length of the base at regular half-inch intervals to give slots for the cord to sit.[8] The early trials with the new boards have been excellent: they are easy to use, and give the ‘correct’ look to the leather on the book. One recent trial was on a particularly difficult job re-backing two books in reverse-calf. The new tying-up boards enabled me to get really clean and even adhesion of the leather across the spine. In the past I have used a finishing press with metal pins along the side for tying-up but the boards were much easier to manage. And of course I now have some beautiful sets of tools which I hope will last for many generations.

Arthur Green, February 2023

[1] Lena Krämer left Green’s Books in November 2022 to join the University Library in Graz, Austria. We miss her very much and wish her well in her new conservation role.

[2] As it transpires our trip was well timed; since writing this blog Trevor had downsized and the shop has closed. Trevor has a new, smaller bindery at home.

[3] Typical features of the ‘Romanesque’ style are: wide double-thong supports, wooden-boards covered in a white tawed skin, a flat back/spine, and sewing supports laced into the thin spine edge of the board.

[4] Typical features of the ‘Gothic’ style are: Thick double-cord supports, cushioned wooden-boards covered in tawed or tanned skin, a rounded back/spine, and sewing supports laced into the outer face of the boards.

[5] Middleton, A History of English Craft Bookbinding Technique, p. 155.

[6] Middleton, A History of English Craft Bookbinding Technique, p. 156.

[7] Hasluck, Bookbinding, p. 61 (Note: there is a similar image in Crane, Bookbinding for Amateurs, p. 128.

[8] I’m aware that I have mixed imperial and metric measurements when describing the boards; I would usually use metric but it’s clear that the boards were initially made to imperial dimensions so I worked with that – the half inch spacing for the notches was just right.

Thank you. A good article.

Very interesting and relevant. Thank you!

Thanks Nicolas, we’re glad you enjoyed it.