In July 2023 we were visited by a family looking to conserve their copy of a Guru Granth Sahib Ji which had been in their family since 1984. The Guru Granth Sahib contains the central teachings of Sikhism as laid out by the ten Gurus. This text is revered as the eleventh Guru and is therefore treated with the same level of veneration. Due to the sacred nature of the text we contacted volunteers at the Pothi Seva, to gain further insight into its structure. Located at the Singh Sabha Gurdwara in Southall, West London, Pothi Seva is a charity dedicated to the preservation and conservation of Sikh texts.

This publication of the text was printed in 1983 in Delhi, India and has been stab-stitched and showed many of the hybrid structural features that are common in Islamicate bindings of this period. The binding featured western characteristics such as squares, marbled edges and a western style single core, two coloured endband with a front bead. It also featured aspects of Islamicate bindings such as a fore-edge envelope flap, flat spine and cuboid shape[1].

As Sikh prayer books are intended for regular use it was very important for all conservation and repair work to be structurally stable. In advance of practical conservation work, Jasdip’s chapter on Sikh Bindings in Conservation of Books (2023) was referenced to provide further context and understanding of the traditional requirements and historic binding styles appropriate for such sacred texts.

This conservation project was a collaboration of ideas and practical skills between myself and Arthur. I have highlighted below three areas of work undertaken which I believe are of particular interest and show the skills and thought processes behind this project.

Sewing

One of the biggest problems presented by this book was its stab-stitch sewing structure. Due to its constant daily use a number of folios at the centre of the text-block had become detached and others were at risk of detaching in the future. In addition, the protrusion of these leaves from the fore-edge was causing additional damage to the paper due to it rubbing against the fore-edge flap.

In order to rectify this issue it was decided that the best course of action would be to re-sew the text-block, removing the original stab-stitched cord and sewing onto tapes. This in itself presented new obstacles as the Guru Granth Sahib Ji has 1430 pages, or 358 folded single folios. Not a small amount of re-sewing! In addition, we were conscious about adding too much swell at the spine from the additional thread, and preserving the original marbled edges.

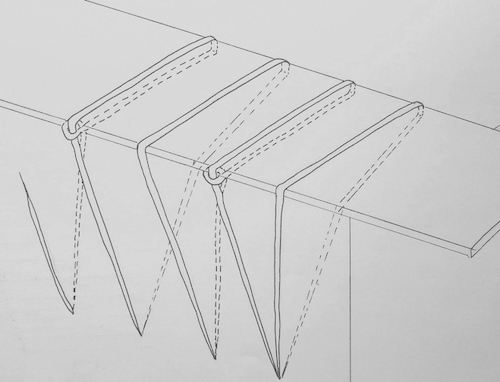

Taking all of this into account, it was decided that the single folios would be sewn 4-on using seven sewing stations. This allowed two points of contact on every folio while reducing the quantity of thread, and therefore swell.

In order to ensure we kept the beautiful marbled edges, so indicative of this binding, we used a knocking down iron at the head of the book during sewed to ensure a flush edge. This worked fantastically well with the final edge being almost indistinguishable to before its re-sewing.

Historically when sewing so many sections on at one time, each section may have only been sewn through once. While we needed to reduce the swell we also wanted to ensure the text could withstand being opened multiple times a day for generations to come. To keep the swell to a minimum we used 35/3 linen thread and seven thin 7mm linen tape supports. This resulted in only 9mm of additional swell at the spine compared to the fore-edge. While this is not negligible, and would not be appropriate for some books, it was within our binding allowance and enabled a much stronger underlying support to ensure the longevity of the text.

Spine Stiffeners

A unique feature of Sikh bookbindings is their prominent spine stiffeners. These were used to reduce mobility in the text-block and limit the opening of the text to around 100 degrees to protect the sewing and prevent the spine from concaving.[2] Historically these may have been made from thick board or a board and paper laminate and would have been adhered to the spine and then covered with a woven fabric lining.[3]

While our re-sewing of the book onto tapes created a stronger underlying sewing structure, it also allowed the book to open much more easily, which in this case, given its size and constant use, was not desirable. The number and dimensions of stiffeners varies greatly in historical examples so there was scope for us to choose what was best for this particular book.

We decided to use four stiffeners in total. These were made of a laminate of paper and parchment to create a much stronger and rigid stiffener. A linen liner was added prior to attaching the stiffeners to provide additional support to the text-block and reduce mobility on opening. Two stiffeners were attached near the head and two near the tail of the spine, between the sewing tapes. Each stiffener was attached firstly with EVA but we felt that an additional method of attaching them to the spine was needed to ensure a truly strong support.

Given the hybrid western and Islamicate nature of the original binding, we felt that using a traditional western technique of tacketing, found on stationary bindings and used since the 16th century, would work very well. The technique uses 2 holes punched through each of the stiffeners through to the centre of a folio and a secondary parchment stay inside the fold which is then sewed through twice, finished with a knotted tacket using 25/3 linen thread, and EVA added to add extra security.[4] Each stiffener was attached to the spine with six tackets at equidistant positions. This structure was successful ,allowing the book to open but also created a good level of rigidity and support.

Woven Chevron Endband

Originally this book was bound with a western style endband. This consisted of a rolled paper core, worked with blue and gold threads, with a front bead. It had only three tie-downs, one in the centre and one at either end stabbed through the sides of the text-block and tied at the spine. The use of western style endbands became more common in Islamicate prayer books made during the mid-19th to the mid-20th century in India due to the British rule of the Indian subcontinent and the decline of traditional bookbinding techniques.[5]

Given the significance of this book to the family, we felt that a traditional woven chevron endband would be more appropriate. One particular issue with traditional Islamicate endbands is that the core can fall off the back of the book when opened and cause the thread to cut into the spine folds. To counter this, and create a more stable and durable endband, we decided to adapt a traditional Islamicate endband. This would be both more visually in keeping with traditional Sikh bindings but also provide structural support.

In order to create this endband we incorporated the technique of looping the primary sewing thread around a core, Fig 5a., with a back bead, Fig. 5b. (Note, in this instance our use of the term back bead denotes a wrapping of the thread around the outer tie-down which acts as a locking mechanism, opposed to a crossover and change of threads as is stereotypical of a front bead). This technique offers flexibility and strength and stops the core from dropping off the back of the book, keeping it nicely flush to the spine. [6]

By alternating the two types of tie-down it enabled the core to be held firmly down against the head/tail of the text-block and also prevented the core from dropping off the back of the book.

Anna-Marie Beauchamp, August 2023

[1] Dhillon, J. S. (2016). ‘The ‘Pothi Seva’ Endband’, Bookbinder: The Journal of the Society of Bookbinders, vol. 30, pp. 47-52.

[2] Dhillon, J. S. (2023). ‘Sikh Bindings’, in Bainbridge, A. Conservation of Books. Oxon: Routledge, p. 113.

[3] Dhillon, J. S. (2023). ‘Sikh Bindings’, in Bainbridge, A. Conservation of Books. Oxon: Routledge, p. 113.

[4] Szirmai, J.A. (1999) The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding. Surrey: Ashgate, p. 8.

Boudalis, G., Miller, J. and Song, M. (2023). ‘The Birth of the Codex’, in Bainbridge, A. Conservation of Books. Oxon: Routledge, p. 8.

[5] Dhillon, J. S. (2016). ‘The ‘Pothi Seva’ Endband’, Bookbinder: The Journal of the Society of Bookbinders, vol. 30, pp. 47-52.

[6] Green, A. (2019) Endband Mechanics. Available at: https://www.greensbooks.co.uk/2019/02/28/endband-mechanics/ (Accessed 15 August 2023).